Kafka's Nightmares

June 13, 2024

The association of Kafka’s name with the word “Kafka-esque” contributes to a fundamental misunderstanding of his work. The term was likely coined in earnest good faith, but has been morphed to represent only a small and rather shallow aspect of Kafka’s novels: the irony inherent in the illogical nature of machine-like bureaucratic systems ostensibly built on logical principles. While this is certainly a theme in such works as The Castle and The Trial, the specific machinations are far less important than the experience of the main character caught within them, which is characterized by an almost paralyzing anxiety. This anxiety gets to the real heart of Kafka’s work, with its presence felt in almost every one of his short stories.

An important characteristic of Kafka’s work that can not be ignored is the fact that the vast majority of it is unfinished, and in all likelihood unfinishable. It becomes eminently clear early on in each novel that there is no possibility of resolution, and that essentially unrelated events will continue to follow each other until there are simply no more pages left. Many of his stories are clearly descriptions of his dreams, and either end when he woke up or when he forgot what had happened next.

The dream-influence is most clear in the way his stories tend to begin. A character will find themselves in a situation. The character is not initially described, only the situation. As the scene continues, the character sometimes will reflect on how they got there, constructing his backstory as one constructs the world of a dream as it is happening. In a dream, you will be searching through a room for an object... it will occur to you that the object you’re searching for is a book... the book is the photo album you had when you were a kid... you realize that you’re searching in your parent’s attic… and so on. The situation comes first, and the world second. The world is created in response to the situation. The world includes the character involved in the situation.

This is made explicit in stories such as “Descriptions of a Struggle.”

“Only when the sky became gradually hidden by the branches of the trees, which I let grow along the road…”

“…since, as a pedestrian, I dreaded the effort of climbing the mountainous road, I let it become gradually flatter…”

In this story, the narrator is designing the world consciously, as if lucid dreaming. More often, the relationship between the world and the character is more antagonistic. In “A Country Doctor,” the titular narrator finds himself without a horse and carriage when he desperately needs to visit a patient across town; thankfully, two horses, along with a carriage and groom, emerge in clown-car-esque fashion from an unused pigsty in his yard. But the groom is a scoundrel, and immediately sets off after the doctor’s servant girl, and the doctor's anxiety for her safety follows him throughout his desperate visit to his patient (whose house he instantaneously emerges at as soon as he sits down in the carriage.) The story ends when the doctor sets off for home, only to find his horses trudging forward at a glacial pace, crawling through the snow, ensuring that he will never reach his destination.

Regular dreamers will be familiar with the tendency of dreams to devolve into nightmare. Sometimes, this is the result of a growing unresolvable anxiety, such as the doctor’s concern for the servant girl he left at home; and sometimes it happens all of a sudden and for no reason at all. The latter is the case in my favourite of Kafka's dream-stories “The Judgement,” in which the narrator’s decrepit dad suddenly bursts violently to action, berating his son for his utter depravity, and sentencing him to death by drowning (upon which the son dutifully dashes out of the house and tumbles off a bridge.)

This dream-effect is masterfully carried off in his novels and certain stories, but in other stories, the dreams, being inherently illogical, fail to cohere into anything meaningful. The power of a dream is that one’s emotions are heightened, that the absurdity of the situation and its lack of connection to mundane reality allows one’s feelings to be somehow pure and unhindered. The desperate frustration of trying to climb a slight incline as your legs collapse beneath you; the despondency of finding that all your friends and family have kept you in the dark for years (about what? and why?); the elation of discovering a hidden truth that will unlock all the potential you have left squandered throughout your sorry life! All this is untethered from the daily mundanity of eating and breathing and working. You’re not wondering what you’re going to do tomorrow, or what you did yesterday, because there is no tomorrow and there is no yesterday.

However, when described factually, dreams are incoherent streams of events and feeling that mean little to anyone but the dreamer. The least effective of Kafka’s stories are those that are merely dreams. Dreams provide wonderful material for molding into stories, but the molding must be done, whether this means trimming the extraneous detail or capturing the emotional essence and transplanting it into a more cohesive story.

At a certain point in “Wedding Preparations in the Country,” an early unfinished story, when the narrator is dreading his visit to the country, he ponders how he used to handle such situations as a child, when he would pretend to send his body away, while the real him continued to lie in bed.

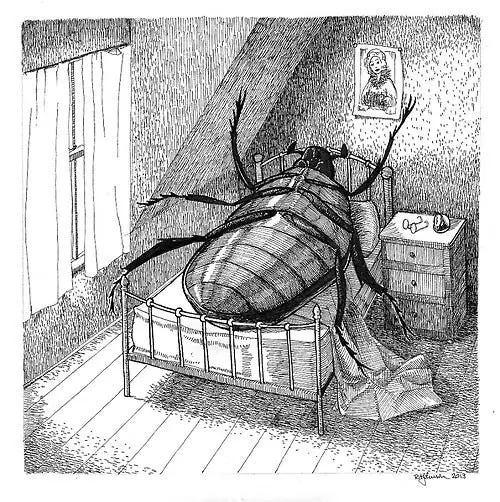

“As I lie in bed, I assume the shape of a big beetle, a stag beetle… The form of a large beetle, yes. Then I would pretend it was a matter of hibernating, and I would press my little legs to my bulging belly. And I would whisper a few words, instructions to my sad body, which stands close beside me, bent. Soon I shall have done it — it bows swiftly, and it will manage everything efficiently while I rest.” (56)

This image of a bedded individual transformed into a beetle will be familiar to anyone who’s read Kafka’s most famous story, “The Metamorphosis”. And it provides a vital clue to the nature of that story, for it proves that this idea was not a spur-of-the-moment whim of Kafka’s, but a deep-seated response to dread and fear: specifically the dread of having to go somewhere uncomfortable. In the childlike imagination of the narrator in “Wedding Preparations in the Country,” the beetle-body’s immobility is a source of comfort and security, as it means the narrator does not have to go where he does not wish to. However, for the salesman Gregor Samsa in “The Metamorphosis,” this is complicated by the fact that he is a grown man with responsibilities to his family and his company. These responsibilities force him, in some sense, to desire to leave his bed, but this desire is totally alien to his emotional side, which wants nothing more than to lie down and rest. This alienation between body and mind is manifested in the beetle-body that he literally can not control.

What makes the story so masterful is that it thrusts this illogical situation out of the dream-world and into reality. Following Gregor’s fantastical transformation, everything that follows is an entirely logical extrapolation of his circumstance. The reactions of his family, his boss, and the strangers that end up seeing him, are outright reasonable. His family specifically, who have to deal with his situation most directly, are shocked at first, but eventually come to terms with the fact that they must now somehow live with this creature that was once their son and brother. They clean his room, feed him, and in response to his inability to bring home a salary, find work in order to support themselves.

This is more than a simple what-if scenario, and the reason is because the crux around which it all springs is purely emotional. The plot functions like a machine or an algorithm; once it has the initial input, it simply rolls along. That input, however, is a complex of dread, guilt, fear, and self-doubt.

The initial aspect is immediately relatable: you are lying in bed, knowing you have to go to work, but you simply can not get your arm to toss aside your covers and your legs to fall off the side of the bed onto the floor. You know you must do it, and sooner rather than later, but it’s as if the connection between your impulses and your muscles has been severed.

As the story goes on, there emerges an additional layer: in some sense, Samsa wants this disfunction to be explicable, to be the result of an illness that is not his fault. He wants the doctor to show up and tell him that he’s sick and must be taken care of, and that he's not to blame for oversleeping and being late for work. Once it becomes clear that he will gain neither sympathy nor reassurance, the guilt emerges. Clearly, he thinks, his family will starve and suffer without his support, and in some crooked way, he is to blame for his transformation, and therefore their suffering.

But the final tragedy of the story is that his family ends up thriving, and the company Samsa works for forgets about him entirely, proving that he was not indispensable at all, but in fact a burden on the world. This final fact is the manifestation of a deep-seated self-loathing.

The frictionless way the story succeeds on both an emotional and a literal level strengthens both aspects. While Kafka’s dream-stories can occasionally suffer for their inscrutability, it can also be said that stories rooted in realism often suffer for their normalcy. “The Metamorphosis” is the result of transforming emotional states into an initially absurd situation that gradually becomes “real.” The absurdity is the exaggeration that immediately hooks the reader, while the realism compels us forward into the deeper recesses of Samsa’s psyche.

The core mechanism underlying all of this is extrapolation. We begin with a premise, and then explore the consequences of the premise. The game of action and reaction between Samsa and his family continually adds new dimensions to the story. Samsa is not only visibly transformed, but he also emanates a nasty odor, leaves a gross film on all the surfaces he crawls around on, and only desires to eat rotten food. He crawls around on his spindly legs, and eventually takes to lying around on the walls or ceiling. All of these are perfectly natural consequences to transforming into a beetle, and they only serve to further his alienation from humanity.

We see a reversal of this alienation in the story, “A Report to an Academy,” which takes the form of a transcript of a speech given by a socialized ape. The ape explains its capture in West Africa, and the ways it learned to emulate the crew of the ship that carried it to Europe. At the time of the speech, the ape has become essentially human, a fact that fills him with as much disgust as pride. The ape had no desire to become human; it was his only means of survival.

The premise is initially absurd. We have this ridiculous image of an ape in human clothing standing behind a rostrum orating to what we can imagine to be a crowd of suited professors listening intently. However, the ape presents his story so matter-of-factly that its internal logic starts to make sense. Of course an ape in his situation would learn to emulate humans; he had no choice! The fact that such a thing has never occurred in the long history of humans imprisoning primates starts itself to seem strange. Once we’ve accepted his story, we can start to sympathize with the ape. His feelings of alienation and disgust start to make sense. By the end of ten pages, the image is no longer comically ridiculous, but dignified and tragic.

The contradictory combination of playfulness and seriousness; logic and illogic; dream and reality creates the wonder of Kafka’s worlds. It is too simple to call it dream-logic, because dream-logic only makes sense to the dreamer. Kafka manages to convert dream-logic into a new form by imbuing it with a more universal pathos that allows us in our waking and sober state to become wrapped up in the dream. Kafka’s stories often take place in the most dull and drab environments possible: a dreary apartment, an office building, an auditorium, a small village, the sidewalk of an undifferentiated city. They feature bored characters whose only goal is to get on with their mundane lives. When fantastical events occur, it doesn’t please anyone. They don’t gasp in wonder. Instead, they get annoyed, because they’re trying to get to work and suddenly there’s a pair of magical bouncing balls in their apartment that won’t go away.1

There’s a fun & games aspect to Kafka, but it’s always undercut by a serious attitude toward life: a crushing sense of responsibility toward family and society. The whimsical does not prevail in the end. It is not an escape from the drudgery of everyday life. The whimsical can do nothing but stop the gears of the grand machine for a moment, before being crushed and cast aside.

A humanized gorilla is not a wonder; he is just one more sad man. A man who must perform his job in order to make money in order to live and eat and breathe. Gregor Samsa’s transformation is initially freeing — he doesn’t have to go to work today! — but without his work, he’s just a useless burden on his family. Even in his wildest imaginings Kafka can not imagine his way out of this sense of duty, and its associated guilt.

HP Lovecraft, an American contemporary of Kafka, similarly deals with themes of fantastical escapism in many of his short stories. The chaotic depravity of the modern city (a problem that is often associated in his stories with immigrants) causes one to yearn for the epic majesty of ancient times. Dreams carry his characters into mind-defying worlds, where anything is possible. The fact that these worlds are terrifying and fatal is less important than the comfort in knowing that they are there; that there is in fact something bigger and older and more significant than this puny stupid world we reside in.

Stories such as “Celephais” and “Ex Oblivione” seem to warn against losing one’s self in such escapist fantasies, but Lovecraft’s stories never offer any reasonable alternative. There is very rarely any distinct sense of the “real world” in Lovecraft’s stories; it only exists as an ugly and dreary counterpart to dreams. There are scholars who drive themselves crazy attempting to decipher forbidden knowledge, like wizards of old; and there are the ignorant bestial commoners who cling to superstition and are more often than not intimately connected to demonic entities. In the end, Lovecraft’s whole conception of the world feels like the fantasy of a lonely, isolated individual.

In contrast, Kafka’s sense of isolation feels all the more grounded in our shared reality. The grand irony is that he is not alone in his alienation; we all, to a certain extent, share it: this feeling like there’s a massive machine we’re a part of that we can neither meaningfully stop nor meaningfully accelerate. We can’t help nor harm it, because it already occupies both extremes: it is cruelly efficient and hopelessly inefficient at the same time. This is the absurdity that torments someone like Gregor Samsa, whose desire to escape and desire to contribute are both so powerful that they create a logical paradox and turn him into a beetle.

I think Kafka suffered from this very paradox, and this contributed to his inability to complete or gain satisfaction from his stories. It seemed that he longed for the freedom to dream, to fully immerse himself in fantasies, but his dreams always ended up tainted by his bitterness and self-loathing. There was always too much of The World in them. At the same time, there is a seriousness to his attitude, a steadfast commitment to fiction-writing, that must have made him feel ashamed of all the silliness and humour that found its way into his fiction. It is the curse of someone so immersed in the paradoxes of the human condition to never understand themselves or the power of the work they do.

It’s no secret that Kafka was deeply dissatisfied with his work. The famous story goes that he asked his friend Max Brod to burn all his papers after his death. This is occasionally interpreted as a grandiose gesture, and that’s probably fair. Great shame is often the inverse of a greater pride. Many writers have grand ambitions that propel them forward, and a belief that they can accomplish something magnificent. This belief is strengthened by the fact that they can never, ever, understand whether they’ve succeeded or not.

Kafka managed to imbue his stories with the unique character of his own emotional state, while at the same time capturing a near-universal sense of alienation. But he could only read them as Franz Kafka. He couldn’t tell whether he had successfully communicated what it meant to be Franz Kafka, because he already knew beforehand. He couldn’t know that other people could relate to the form of his suffering, because no one else had written the stories of Franz Kafka.

It is perhaps the sorriest fate to have one’s words — or even one’s name — absorbed into a dictionary. I wished at times in this essay to discuss Coleridge’s “suspension of disbelief,” but the phrase has become so overused at this point as to become mere sounds. “Kafkaesque” is used to describe a bad customer service experience at the bank, when what we are really talking about is a minor inconvenience or a waste of time. Kafka’s stories are not just absurdities, and they are not concerned with mild frustrations. Instead, they present the totality of modern life, the ways in which all these social systems collide to create despair, fear, anxiety, and hopelessness.

Because if you get down to it, there is a deeper horror to a bad experience at the bank — one that can be explained via Kafka’s work. The bank is an institution you rely on for the money you need to live and eat and breathe — the money that you drudge away at work in order to earn — and if they fail in their responsibility to allow you access to that money, you are in serious trouble. Your life is in their hands, and yet it seems that despite their grave expressions, they take their job horribly unseriously, allowing their esoteric procedures to twist themselves into unloosable knots that prevent the person you are talking to from doing anything at all, and even prevent them from caring one way or the other, leaving it all up to you to fight for the thing that you worked for and entrusted to them while not even understanding how! And meanwhile you still have to get to work! And your boss is insane and incomprehensibly furious! And your subordinates (if you have any) are children! So who’s gonna blame you if sometimes you just want to lie in bed and imagine you’re a fucking bug!